|

Central

Asia, a stronghold for dictators, poverty and corruption,

doesn’t at first glance seem to offer fertile ground for high

investment returns. But this is precisely what some of the

region’s more intrepid investors hope to find and profit from.

Kathryn Wells spends a week on the road with two hedge fund

managers, on the lookout for opportunities on this new

frontier.

Bids and offers in

no-man’s-land

THE

ROUTE TO the Kant Cement-Slate Plant from Bishkek, the capital

of Kyrgyzstan, is a bumpy 20 kilometres. And our car, which

carries foreign number plates, is likely to attract unwelcome

attention from the notorious traffic police, known by their

Russian acronym GAI, stationed along the route. THE

ROUTE TO the Kant Cement-Slate Plant from Bishkek, the capital

of Kyrgyzstan, is a bumpy 20 kilometres. And our car, which

carries foreign number plates, is likely to attract unwelcome

attention from the notorious traffic police, known by their

Russian acronym GAI, stationed along the route.

After

some discussion about what’s best to do our host has agreed to

send his SUV, bearing official government plates, to accompany

us on our journey. We weave our way through the traffic at

will, paying little attention to oncoming vehicles. Those

police who do contemplate stopping us have second thoughts

when they see the car heading our mini-convoy. They melt away

into the background. Sometimes, it seems, the system has its

advantages.

We

pull up at the plant, its spluttering chimneys sharply

highlighted against the blue of the sky and the white of the

snow-capped mountain range behind it. The snow on the mountain

peaks never melts, not even in the burning 40ºC heat of

summer. The thought crosses my mind: what exactly are we doing

here?

It’s

the final day of a week-long trip around central Asia,

accompanying two hedge fund managers as they tour the region

on the lookout for new investment opportunities. And cement

might prove to be a good investment, as demand for building

materials across the region looks set to

rocket.

Kant

Cement is one of five cement companies spread across Russia,

Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan that is ultimately to be

packaged into a holding company and listed, in all likelihood

on a London exchange.

Demand

for cement is huge, particularly in Kazakhstan, where the

government is engaged in the construction of its new capital,

Astana, from scratch. Afghanistan is also expected to become a

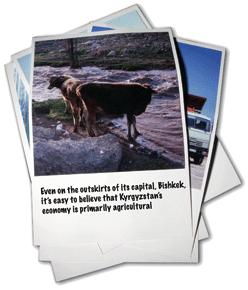

big importer, along, of course, with China. Kyrgyzstan is a

poor, mountainous and largely commodity-free state nestled

between China, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, and this

factory could well prove to be one of its most profitable

enterprises.

The

plant’s general director, Adal Issabekov, was transferred here

from one of the Russian cement companies in the group earlier

this year, with a mission to get the factory working to its

full capacity before a listing plan is taken any further.

Kant

was one of the largest cement producers in the USSR and,

despite ageing equipment installed in 1962, it is in

reasonably good condition, Issabekov says.

To

falling jaws all around the room, he then proceeds to tell us

about the factory’s other product – artificial slate. “It is

not used widely in Europe, I know,” he says, “as ecologically

speaking, it is not very politically correct. One of its main

ingredients is asbestos. However, there is a huge demand for

it in this region.”

Our

western attitudes make us baulk at this use of something so

injurious to health. Yet it is clear that for the local

population, who face temperatures of minus 25ºC and below

every winter, such concerns are secondary to having a warm

roof over their heads.

We

express the hope, at least, that this will prove to be a

market with a finite lifespan. “As the population gets richer,

demand will certainly drop,” Issabekov agrees.

At

the moment, Kant is Kyrgyzstan’s only cement producer, and the

country’s anti-monopoly commission that regulates it ensures

that most of its production is destined for domestic consumers

at below-market prices.

However,

the government is building a new cement plant, and once Kant

is no longer a monopoly it can take full advantage of higher

market prices abroad in such places as Kazakhstan.

We

are invited to take a tour of the plant and jump in a minibus,

accompanied by the chief engineer. On our way round, we cannot

escape a visit to the slate production line, including a

warehouse where thousands of bags of a white-looking substance

– asbestos – are piled high up to the roof. The chief engineer

pooh-poohs our questions about its safety, saying that he has

worked in the plant since the 1960s with no ill effects. But

as he finishes saying this he breaks into a spasm of coughing;

it does nothing for his argument. We

are invited to take a tour of the plant and jump in a minibus,

accompanied by the chief engineer. On our way round, we cannot

escape a visit to the slate production line, including a

warehouse where thousands of bags of a white-looking substance

– asbestos – are piled high up to the roof. The chief engineer

pooh-poohs our questions about its safety, saying that he has

worked in the plant since the 1960s with no ill effects. But

as he finishes saying this he breaks into a spasm of coughing;

it does nothing for his argument.

The

new adventurers

The

Diamond Age Russia Fund is one of the few hedge funds

operating on this new frontier. Just 14 months old, and still

growing, it recently became the first international

institutional investor to buy into the corporate bond market

in Uzbekistan. Today, it also holds nine Uzbek equities, with

a total Uzbek allocation of 6% of the fund spread between

different bonds and equities, meaning that no position is

worth more than 0.5% of the total fund.

It

also boasts investments in Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan,

Turkmenistan, Ukraine, Georgia and

the Baltic States as well as its core market of Russia. Its

strategy is to invest in the stocks and bonds of any company

that has most of its assets, revenue growth or net income

growth in one of the countries of the former Soviet Union,

regardless of where they are listed. It also invests in

derivatives in currencies, interest rates and commodities. The

fund’s key investment professionals, Slava Rabinovich, a

former head of leading private Russian bank MDM’s asset

management arm, and previously an assistant portfolio manager

and head trader at Hermitage Capital, the largest public

equity investor in Russia; and John Winsell Davies, previously

a director of Alfa Capital and a managing director of Franklin

Templeton Investments, are constantly on the lookout for new

opportunities.

They

believe that central Asia might offer these. It is a region

where first-mover advantage is everything. By the time the

hedge fund community at large has cottoned on to the yields

that a market can offer, the type of returns that allowed a

pioneer to produce a more than 82% return net of fees for

investors during its first 14 months of operation have already

begun to be eroded.

Emerging

markets have enjoyed a spectacular run in the past few years,

buoyed up by the global search for yield and the absence of

crises in any of the major economies such as Brazil, Russia

and Turkey. Yet this just serves to highlight the gulf between

these economies and some parts of central

Asia.

Diamond’s

managers have agreed to let me spend a week on the road with

them as they travel around the region assessing some of the

holdings in their current portfolio as well as new investment

opportunities. The trip begins in Tashkent, the capital of

Uzbekistan.

Heading

east

Tashkent,

like all the major cities in the region, suffers from a legacy

of crumbling Soviet-era housing blocks that disfigure the road

from the airport into town. Half the cars on the road date

from the same era, ancient Ladas or Skodas that look as if

they are held together with pieces of string. In Uzbekistan,

the other half – unlike in Moscow or Kiev, where big SUVs with

black-tinted windows dominate – are made up almost entirely of

Daewoos, the product of one of the country’s few large-scale

joint ventures.

You

immediately feel the presence of security officials – hanging

about on street corners or lurking by the business hotels. To

western eyes, these are unfamiliar places. The situation is

not, though, like it was in the late 1990s, when foreigners

travelling here were advised to leave any literature critical

of the regime on their planes.

Even

first thing in the morning of a Sunday in early March, the sun

makes a welcome appearance. The land looks flat and fertile,

although this belies the massive water problems that have led

to a severe drying up of the Aral Sea; it is now split into

two far smaller areas of water that are getting still smaller.

Uzbekistan

has long proved one of the thornier countries in the region

for supranational institutions such as the European Bank for

Reconstruction and Development. Its capital did host the

EBRD’s annual meetings in May 2003, although the institution

selects the venues for its annual meetings as much as four

years in advance. Back in 1999, Uzbekistan’s economic promise

loomed larger than it has since delivered on. The government

has proved obstinately opposed to the reforms and improved

human rights that the west has called for, leading the EBRD to

revise its country strategy for Uzbekistan just weeks before

its annual meetings were held there.

This

raises the question of whether democracy, per se, will really

ever be suitable for central Asia. Uzbekistan’s president,

Islam Karimov, is just one of a number of former Soviet

leaders in the Caucasus and central Asia who have maintained

their hold on their countries more than a decade after the

Soviet collapse. And when states such as the US seem more

intent on keeping geopolitically important countries like

Uzbekistan on side than on wholeheartedly promoting democracy,

it seems it is unlikely to become a priority in the medium

term.

Human

rights abuses and the flourishing of democracy, though, are

not at the top of an investor’s list of concerns. Stability

and the ability to repatriate profits are.

Meetings

in Tashkent have been arranged by Ansher Capital, one of the

few investment banks to operate in the region. Ansher’s chief

executive officer, Alisher Djumanov, who has more than 10

years’ investment experience, with Credit Suisse First Boston,

Renaissance Capital and Ernst & Young, gives us an

overview of the country.

Uzbekistan,

he says, has vast potential. It is the most populous country

in the region, with 26 million people, and is situated in the

heart of central Asia. It recorded GDP of $12.8 billion in

2005, $492 per capita. Like many of his contemporaries

throughout the former Soviet states of the CIS, Djumanov has

returned to his native country after years working in the

west, more convinced than ever of the fundamental potential

that it holds.

Our

first company meeting is with Alskom Insurance, Uzbekistan’s

sixth-largest insurance company – there are 26 in total – and

one of the country’s biggest private insurers. The firm has

completed four share issues, offering a return on equity in

the region of 40%. The money has gone towards increasing its

capitalization, in line with new government requirements.

Like

much else in Uzbekistan, the insurance market is in its

infancy. The whole region is acutely underinsured – in Russia,

for example, the average insurance spend is about $120 a year.

Even this, though, compares favourably with the $1 a year or

less per person spent in Uzbekistan.

It’s

difficult to question the growth possibilities; what is less

clear is the timescale needed to realize them. Luckily for

Alskom, president Karimov has said that the market will grow

five-fold in the next five years, although it is not clear

whether or not this will fall by the wayside, as have other

similar presidential decrees.

We

adjourn for lunch to a Chinese/African restaurant described in

the Lonely Planet travel guide – Michelin guides having not

yet reached this far – as a “restaurant with an identity

crisis”. The owner, apparently, is delighted with this review.

Over

lunch we talk about the region more generally. It seems that

there is a natural order to things – just as the British make

jokes about the Irish, or the French about the Belgians, so

Uzbeks make jokes about the neighbouring Turkmen. “We sent a

few people there to do some research,” someone jokes.

“Unfortunately they never came back.” Given what the limited

information coming from Turkmenistan suggests these days, it

looks as if there’s many a true word spoken in

jest.

Cautiously

optimistic

After

a whistle-stop tour of the city after lunch – a particularly

ferocious series of earthquakes in 1966 ensured that few

historical buildings remain intact – we move on to a meeting

with the head of the American Chamber of Commerce in Tashkent,

Donald Nicholson. Nicholson also runs the Central Asia Small

Enterprise Fund, one of the few known private equity investors

into the country.

Nicholson,

a CIS veteran, describes himself as “cautiously optimistic,

couched on the need for certain things” when pressed on his

outlook for the country. The list of these “certain things”,

though, is long, spanning the “acute” need for reform of the

banking sector, a change in tax legislation and so

on.

Cotton,

textiles, food processing and mining are sectors, he tells

us, that should expect investment.

The country has “tremendous mining potential”. He laments the

reasons that have kept big mining groups, such as Rio Tinto or

Anglo American, out of the country so

far.

He

also explains that while the country has a population of 26

million, foreign companies operating there, such as British

American Tobacco, believe the consumer base for their products

is much smaller, perhaps as little as 200,000. He also tells

us that of the 26 million, as many as 3.5 million are

estimated to work abroad. It is this Uzbek diaspora, spread

throughout the west and the Middle East, which regularly

repatriates the money that to a large extent supports the

economy and forestalls its total collapse. Reasons for leaving

the country are obvious – Nicholson says that an

English-speaking graduate can expect to earn about $120 a

month as a receptionist in a four-star hotel in Tashkent but

could make more like $400 a month in a comparable

establishment in Dubai.

Some

of the problems that Nicholson points to are endemic to the

region. Reform of the banking system is top of his agenda, so

that banks “are not instruments of the tax system. They should

be made to work like in other countries” – a complaint

familiar to anyone who has done business in Russia in the past

10 years, albeit one that very gradually seems to be being

dealt with there at least.

Bureaucracy

is another bugbear that the entire region, central Asia

especially, must face up to.

To

be successful in Uzbekistan today “takes a very special type

of investor,” Nicholson tells us. “You can make good money,

but you have to understand the risks.” In 2005, Uzbekistan’s

largest private commercial bank, Business Bank, lost its

operating licence and was put into liquidation on what

Nicholson calls “completely falsified grounds”. To

be successful in Uzbekistan today “takes a very special type

of investor,” Nicholson tells us. “You can make good money,

but you have to understand the risks.” In 2005, Uzbekistan’s

largest private commercial bank, Business Bank, lost its

operating licence and was put into liquidation on what

Nicholson calls “completely falsified grounds”.

He

says: “We were on the verge of investing, along with the EBRD.

We had both done due diligence. No official reason was ever

given.” The liquidators brought in to oversee the process

turned out to be the bank’s former managers, he says, further

muddying the process.

“If

you are thinking about investing,” he says, “and see that the

EBRD is close to investing, and then this happens, well anyone

else must factor this in.”

This

lack of ground rules does allow for serious profits to be

made, if investors are canny enough – and sufficiently lucky –

to pick suitable targets. “Where else can you buy assets as

inexpensively as here?” Nicholson asks. “There are some very

good opportunities, but if you are a publicly traded fund and

one day the bank you invest in loses its licence, then what

can you do?”

Nicholson

hopes that Russian investors into Uzbekistan might be more

successful at getting their voices heard than their western

counterparts. “Russian investors are echoing the same things

that the West has said about Russia in the past,” he tells us.

“So, maybe the government will start to listen to the Russians

on business matters.”

Speaking

as a strategic investor, Nicholson says: “If you think things

here are bad, then you shouldn’t be here. Our business is

doing well. What is lamentable is that there is so much more

potential, if only a few things were to change. There are

opportunities right across the board, especially in the

extractive industries. There is a case for letting the private

sector in.”

Even

basket-case Turkmenistan, whose human rights record makes

Uzbekistan look positively saintly, has investment in its

natural resources sector through such production and

exploration companies as Petronas, Burren Energy and Dragon

Oil. “If they can be in Turkmenistan, why not here?” questions

Nicholson. “Nothing attracts others like a success story.”

We

jump back into our Mercedes-Benz and make our way to the next

meeting – with the Uzagromashservice Association. The floor of

the entrance hall is being relaid as part of what appear to be

extensive renovations, so we have to hop between pieces of

cardboard laid down to protect us from the dust. Members of

the association, we are told, provide machinery services to

the agriculture sector, and employ 32,000 people. The

association has funded its growth through commercial loans

from local banks but is now looking to sell a stake to

investors. Its main objective is to attract foreign

investment, and the new technology that this is likely to

bring with it. This, the association’s representatives say, is vital because

Uzbekistan is an agrarian country. So far, most interest has

come from Russian investors, although companies from Germany,

Norway and the US are also said to looking at the

opportunities. One example of a member company for sale is an

engine repair firm located in Tashkent in which the government

is offering a 23% stake. A Russian joint venture already owns

a controlling stake in the company.

Chunks

of shares in some of the companies are being traded on the

secondary market, and are of interest to an adventurous fund

such as Diamond.

According

to the association representatives, in cases of strategic

sales on what they call the “primary market”, the price is

calculated and fixed by the state property company. On the

“secondary market”, however, the share price can be

negotiated.

Our

final meeting of the day is with a local banker, who requests

that his name not be disclosed. The average deposit per capita

is around $40, he tells us. “In Uzbekistan, people need more

time to trust banks,” he says.

He

agrees that privatization of state-owned banks must be a

priority. “When the first private bank was set up in 1998, the

state controlled 99% of the market. Today, it still controls

85%. Asaha and NBU must be privatized, otherwise we will see no

change.”

But

one integral problem is that these banks have issued a large

number of loans under state guarantee. The first thing that

any would-be buyer must do is look at the banks’ credit

portfolios, and with many of these guarantees extending as far

as 2015, it might not prove particularly attractive.

The

banker is also critical of the approach of retail lenders.

“Yes, there is demand for good services,” he says. “But what

many banks are doing today, issuing credit cards when people

cannot even withdraw cash, is dangerous.”

The

Golden Road to Samarkand

Uzbekistan

has great potential for tourism, if it can ever fully harness

it. On Tuesday we take a car and drive to Samarkand, the famed

ancient city on the Silk Road to China. The three-and-a-half

hour drive (there is apparently a shorter route that involves

crossing briefly into Kazakhstan, but political disputes

between the two countries mean that the border will not be

open to us) is not particularly scenic until we begin the

approach to Samarkand, when snow-capped mountains suddenly

become visible on our left.

We

share the road with a mixture of cars and occasional herds of

skinny-looking cows. Villages of any size are scarce, and

petrol stations virtually non-existent.

Samarkand,

though, more than justifies the trek. With exquisitely

coloured mosques and mausoleums spread out around the modern

parts of the city, we barely scratch at the surface in the few

hours we have to explore. Our guide, a typical Soviet-era

fount of knowledge, barely stops talking during the entire

visit, offering impressive but ultimately forgettable facts

about the dimensions of every room, and the quantities of gold

used in their construction. We learn about the 14th-century

ruler Amir Timur, known in the west as Tamerlane, who the

Uzbeks seem to regard as a benevolent, fatherly figure despite

his somewhat harsher record for savagely slaughtering subjects

and conquered peoples.

Couple

the attractions of Samarkand with those of other historic

cities such as Bukhara and Khiva, and the chance to explore

the Fergana Valley, the most fertile and most densely

populated region in the whole of central Asia, and tourism

should be booming.

Investment

is clearly needed – both in infrastructure and marketing. The

type of three-star hotels that tourist

groups need are available, although some are still on

the basic side. Investment

is clearly needed – both in infrastructure and marketing. The

type of three-star hotels that tourist

groups need are available, although some are still on

the basic side.

A

region of extremes

Next

day, the flight to Almaty, the former capital of Kazakhstan

that remains the country’s business centre, is scheduled to

leave mid-morning. But an air stewardess announces that

because of a “technical break” at Almaty airport that will

last for one hour we must sit on the plane and

wait.

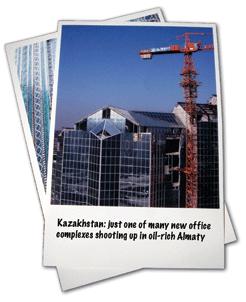

Once

on the ground in Almaty, the difference between it and

Tashkent is striking. Roads are smoother, cars bigger, and

people’s clothes more expensive-looking. Shiny new buildings

are shooting up on all sides, clear evidence of the benefits

of petrodollars to an economy.

It’s

to be hoped that this building frenzy will soon extend to

hotels – one area in which Tashkent does lead its central

Asian counterpart is in business-standard accommodation.

Ironically, the EBRD’s greatest legacy to Uzbekistan appears

to be the plethora of four-star and five-star hotels that

sprung up in response to the bank’s 2003 annual meetings

there. In Almaty, though, we check into a Soviet-era hotel

replete with the heavy furnishings and solemn interiors of

that period.

In

Kazakhstan’s real economy, oil is the only game in town, and

is likely to remain so for many years. The government talks a

good game about diversification but with oil prices where they

are today, the country is enjoying an embarrassment of riches.

In

a sign that Kazakhstan is starting to gain visibility on

international investors’ radar screens, a new Kazakh-based,

but ultimately pan-central Asian, investment bank has just

been set up.

Visor

Capital’s co-founder, Michael Sauer, a veteran of the

Brunswick brokerage in Moscow, meets us in his newly built and

still being furnished offices and takes us out onto the

10th-floor terrace to see close-up the extent to which new

buildings are shooting up. With the sun glinting off the

buildings’ mirrored walls, and a clear blue sky creating a

sharp contrast to the snow-capped mountains that lie just a 20-minute drive away, it is easy

to see what might tempt entrepreneurial bankers such as Sauer

to relocate here.

Dangerous

territory

The

downside, of course, is that this is still central Asia.

Violence within the business community of this relatively

stable “stan” has been escalating, with several notable bank

officials being murdered in recent

months.

We

go to meet Almas Chukin, the former ambassador of Kyrgyzstan

to the US, who today heads the Compass Asset Management

company in Almaty. He is well placed to discuss with us the

relative merits of the stans.

Davies

from Diamond kicks off by saying that the Uzbek market is the

least correlated to the Russian index (RTS) of any market that

his fund looks at. Lack of correlation is a priority of hedge

fund managers regardless of their investment environment, it

seems.

Short-term

Uzbek bonds offer a yield of more than 20%, and the chances of

default in the next 12 months are low. Diamond follows a

basket approach, so a diverse mixture of countries and

products is crucial to its strategy. It has nine equity

positions in Uzbekistan, which account for around 20% of the

fund. These include sugar producers, light machinery companies

and also state-owned Uztelecom, which Diamond uses as a proxy

for the Uzbek market, rather than regarding it as a well-run

company per se.

Last

year’s unrest in the Fergana valley, which the Uzbek

government categorized as “Islamic fundamentalism” and dealt

with particularly heavy-handedly, might prove to be a blessing

in disguise for funds like Diamond, as it will keep out all

but the most adventurous of rivals. Last

year’s unrest in the Fergana valley, which the Uzbek

government categorized as “Islamic fundamentalism” and dealt

with particularly heavy-handedly, might prove to be a blessing

in disguise for funds like Diamond, as it will keep out all

but the most adventurous of rivals.

To

the uninitiated, the situation in Uzbekistan seems pretty

backward. But bankers and investors who have been visiting the

region for the best part of a decade can point to tremendous

changes. “It is as different as night and day,” says Davies

says. “The potholes have gone, the electricity works.”

Diamond

is betting on what Davies calls “a one-way, one-directional

transfer of wealth from west to east.” By this he means the

rise of China, the growing importance of commodity producers

such as Kazakhstan, and the booming populations of many

eastern countries (although few former Soviet republics fall

into this last category). “I can buy stocks [in central Asia]

where the dividend yield on common stock alone is 14% to 18%,”

he says. “And you can repatriate profits.”

One

way to invest in the “trickier” countries in central Asia,

Diamond believes, is through companies domiciled outside their

main area of operations. For example, the fund invests in

several operations in Turkmenistan, but through mining

companies listed in London, New York or Dublin that have a

large proportion of assets there.

The

most fascinating aspect of the trip is the insights it gives

to the different stages that these three central Asian

republics have reached. For western-based investors, it is

easy to lump them together as a homogenous block of far-off

stans. But as Compass’s Chukin explains, their paths since

independence 15 years ago have been far from identical.

His

native Kyrgyzstan was the darling of investors in the

mid-1990s and hailed as an “oasis of democracy”. But the

ultimately poor and commodity-free country, despite having had

one of the most economically liberal regimes in the CIS – it

was the first to join the World Trade Organization and has the

most liberal currency regime – ultimately fell out of love

with its experiment in democracy, and has failed to translate

this into performance. Today it is Kazakhstan that claims that

prize.

Nursultan

Nazarbayev, Kazakhstan’s president since independence, has proven to be one of the

region’s canniest when it comes to economic reforms.

Following

independence, the government engaged in the construction of

new institutions, and subsequently growing its business

sector, up until the double-whammy of the Asian and Russian

financial crises of the late 1990s. Since 2000 it has grown

steadily, with 9% increases in GDP and real incomes up 30% in

the past six years.

It’s

arguable, of course, that this is easy for a country with the

natural resources that Kazakhstan enjoys, which have helped to

cushion the shock for its people of transition from a command

to a consumer economy. Nevertheless, Kazakhstan has

implemented policy changes in areas such as pension reform

that leave it sitting comfortably ahead of many in western

Europe.

Pension

reform is another factor in the country’s favour from the

point of view of western investors. The asset management

business there is still young – the law on investment funds is

a mere 18 months old – but Kazakhs have more than $6 billion

in deposits, Chukin says. This domestic bid will support the

debt and equity markets and should help avoid some of the

problems connected with speculation that countries such as

Hungary have experienced in recent

years.

First

among Kazakhstan’s problems, everyone in the room agrees – and

this is something that affects the region as a whole – has got

to be corruption. There is no point being an honest importer

of furniture, say, and being hit by heavy customs costs, when

you are being undercut by a corrupt competitor.

The

bankers and investors refer to a famous dispute in Russia over

the development of a new Ikea branch just outside Moscow.

Disputes between various local officials meant that it took a

meeting between the head of Ikea in Russia and president

Vladimir Putin himself to get the huge new store open on

schedule.

Visor’s

Sanzhar Kozybayev, an executive director at the firm, then

tells us about a company Visor is working with – a

pharmaceuticals manufacturer called Chimpharm. Listed on the

Kazakhstan stock exchange, the company is the biggest producer

of medicines in central Asia. It makes about 50% of

Kazakhstan’s drugs, in a market expected to grow from $409

million in 2005 to $572 million by 2008, and is focused on

increasing the proportion of its

exports.

Visor

believes that Chimpharm is an interesting investment that can

harness the consumer boom the country is experiencing, and is

working with it to look into the possibility of a further

listing, strategic sale or recapitalization. Diamond’s Davies

says that what is interesting is its potential to increase

exports to the Chinese market. These are the types of

companies offering diversification away from the oil and gas

sector, that funds are on the lookout

for.

We

wrap up for the day and head to a restaurant. As in Moscow,

sushi is all the rage here, and we

are pleasantly surprised by the quality and freshness that

this land-locked country can offer. Almaty’s rich and

beautiful young people are here on display, celebrating the

tail end of March 8, International Women’s Day, which is feted

throughout the former USSR.

The

main game

On

Thursday morning, excited by the thought of our drive across

the steppes to Bishkek in Kyrgyzstan that afternoon, we

prepare to meet an example of the sort of company Diamond

likes to invest in. Max Petroleum is an oil and gas

exploration company initially focusing on Kazakhstan that has

recently completed a listing on London’s junior market, AIM.

Diamond does not invest in Max yet, but its fund managers are

eager to hear about the company’s plans. Ole Udsen, Max’s

Norwegian country manager for Kazakhstan, talks us through the

company’s strategy. Its market capitalization stood at £430

million ($753 million) at the end of January, although this

fell to £260 million in early March after what Udsen describes

as unhelpful research reports, written, he believes, with

little understanding of the company’s situation, and possibly

with the aim of artificially depressing its share

price.

Investing

in an oil explorer entails a fair degree of risk – especially

the risk that the sites it has acquired for exploration do not

eventually yield serious reserves. This, though, argues Udsen,

is offset by the sites’ proximity to two massive fields,

making it more likely that oil will be struck, as well as the

access it has to good infrastructure, and its excellent

government relations. This is an area the company and its

potential investors are keen to underline. Kazakhstan is still

very much a place where who you know is vital to do business. Investing

in an oil explorer entails a fair degree of risk – especially

the risk that the sites it has acquired for exploration do not

eventually yield serious reserves. This, though, argues Udsen,

is offset by the sites’ proximity to two massive fields,

making it more likely that oil will be struck, as well as the

access it has to good infrastructure, and its excellent

government relations. This is an area the company and its

potential investors are keen to underline. Kazakhstan is still

very much a place where who you know is vital to do business.

The

company is still deciding how it will fund its 2007

operations. It is mulling over either a loan or the sale of a

stake in one or more of its projects to a multinational,

although this will undoubtedly mean that it loses an element

of control.

After

the best part of two hours, Udsen leaves. Diamond’s managers

are definitely interested, and will do more

research.

We

adjourn to a vast new restaurant in the basement of a hotel

that promises genuine Kazakh fare. The room is large enough to

be a banqueting hall but we are virtually the only people

there. Our hosts order a selection of delicacies, including

horse meat and a whole pig’s head. Having gorged ourselves, we

get ready to set off for the border and

Kyrgyzstan.

The

drive is spectacular, taking in the vast emptiness of the

Kazakh steppes. To the right, the fields stretch for ever. To

the left, the mountains rise out of the plain like ghosts. Our

driver, Sasha, makes good time across the Kazakh leg of the

journey and it is only when we reach the border that we hit

trouble [see

story].

The

problem with revolutions

The

last day of our trip is also our one full day in Bishkek. We

begin with a meeting at the ministry of finance with deputy

finance minister Murat Ismailov. Diamond’s fund managers do

not yet invest in Kyrgyzstan but are constantly on the lookout

for new opportunities, especially ones that they can spot

ahead of the rest of the market. They are eager to hear what

the ministry is planning, although they view Kyrgyzstan more

as a prospect for 2007 and beyond than as a buy for today.

Kyrgyzstan’s

Tulip Revolution last May, which resulted in the overthrow of

president Askar Akayev, brought the tiny republic – its

population is 5 million – into the consciousness of many in

the west who have never heard of it before.

One

thing that many countries that have undergone such revolutions

have in common though, is that the

upheavals, while opening up the possibility of the type of

democracy advocated by the EBRD, IMF and other such

institutions, can play havoc with the economy.

“Last

year, of course, the economy struggled a bit,” Ismailov says.

“This year, though, GDP growth will be around 5%. The

president wants to see 8%. In my opinion, we haven’t deserved

this fall in confidence. The situation has already

stabilized.”

The

deputy minister takes us through a number of projects that his

ministry is working on, such as the extension of a railway

line through his country that will complete a link between

Uzbekistan and China. Part of the line, from Bishkek to

Issy-Kul, is already in place. Plans are also under way to

convert a military airport near Lake Issy-Kul to accommodate

civilian aircraft in large numbers, as part of a push to

develop the region’s tourist industry.

Issy-kul

is the world’s second largest alpine lake, and its beauty,

combined with that of the spectacular Tian Shan mountain

range, and the possibility of home stays in nomadic yurts,

mean that there is plenty on offer for the more intrepid

tourist.

But

while this is interesting stuff, and it sounds sensible to

mine tourism, there seems to be little immediately on offer

for the portfolio investors.

We

ask instead about the tax code – a new one is being prepared

that the deputy minister claims will do a lot to improve the

investment climate. It includes a flat rate of 10% corporate

and personal tax. The government, he says, understands that

without foreign investment, the economy will continue to

struggle.

But

to some extent its hands are tied – it is working on an IMF

programme that it must stick to rigidly. The country has

nearly $2.5 billion of external debt – huge for a country

whose annual GDP is about $2 billion — and so has few options.

It is in discussions with the IMF about privatization in the

energy sector – although it has few natural resources,

hydroelectricity could be developed much

further.

We

leave the ministry with the feeling that the tiny country is

at the mercy of an institution not famed for its understanding

of the difficulties of implementing fancy Washington-developed

theories of capitalism on the ground. The IMF’s prescriptions

for the rest of the CIS have had at best mixed results, and we

end up hoping rather than truly believing that Kyrgyzstan can

be one of its success stories.

Privatization

perils

After

the unexpected encounter with asbestos at the Kant

Cement-Slate Plant that follows, we form our convoy again and

return to the centre of Bishkek. The sun is shining, and the

temperature a pleasant 18ºC – a million miles, or so it seems,

from the sub-zero climes of Russia.

Tiny

one-storey individual dwellings line the road, often decorated

in a range of bright colours and with roofs of corrugated

iron. In the sunshine their simplicity seems far more

attractive than the Soviet apartment blocks that pervade most

of the region.

The

official number plates on the lead vehicle do the trick once

again, and we reach the centre without incident. We grab some

manti – central Asian steamed dumplings stuffed with meat – to

eat en route, and drive to the offices of the committee on

state property and direct investments, to hear from its deputy

chairman, Anatoly Makarov, about the state’s plans for

privatization.

The

committee is housed in a typical Soviet-style building,

fraying at the edges and with identical looking dingy offices

along every corridor. The committee, representing the state,

is the main shareholder in Kyrgyzstan, as privatization is

still in its infancy.

So

what is the real value of privatization in a country like

Kyrgyzstan? It is certainly no panacea and, in countries ill

prepared for the concept of joint-stock companies and share

ownership, it can be an agent of value

destruction.

Makarov

explains that the first stage towards privatization of

companies in sectors such as electricity generation and

telecoms is to turn them into share companies. The government

then plans to sell them to strategic

investors.

“We

are looking at some plans that will use the stock market in

2006/07, but I do not think that this year will see the sort

of trading that you are interested in,” Makarov tells

Diamond’s fund managers. “We

are looking at some plans that will use the stock market in

2006/07, but I do not think that this year will see the sort

of trading that you are interested in,” Makarov tells

Diamond’s fund managers.

He

says that of the 120 firms that the committee owns shares in,

some 40 are “serious” companies and could be interesting to

foreign investors. This, he says, includes the tender for a

stake in Kyrgyztelecom. He, like Ismailov at the ministry of

finance this morning, stresses the country’s liberal tax

regime and the fact that investors can repatriate profits

without any difficulties.

“We

are a small country, without many resources,” he says, summing

up. “But our time will come. If we meet in a year’s time, then

there will be more interesting propositions for you. Last

year, with the revolution, was very difficult.”

Our

meetings here today in Bishkek seem to have confirmed the

opinion of the two Diamond managers that Kyrgyzstan is a story

for tomorrow, not today.

Although

there are some signs of commitment to developing the capital

markets, there is still some way to go before portfolio

investors will see securities capable of being traded. The

EBRD, Asian Development Bank and similar institutions might be

engaged in projects to develop the stock market but today it

seems that strategic investment offers the more immediate

possibilities.

With

just an hour before sunset, we leap into a taxi to try to cram

in a sightseeing dash around town. Our transport is an

ancient-looking Lada with seats that are barely fixed to the

car’s body. Our driver, a weather-beaten old man chewing

tobacco, is mystified by our request to be taken to a

viewpoint that we have been told about.

There

is no formal viewpoint, he explains, although not wanting to

lose our business he drives us up into the foothills of the

nearby mountain range where we can look back on the urban

sprawl that is Bishkek.

Without

the backdrop of the snow-capped mountains to romanticize it,

it is easier to see the city for the poverty-stricken outpost

in the middle of a vast landmass that it is. Bishkek’s

outlying areas blur into a mix of half-finished building sites

that don’t look likely to be completed soon, and decades-old

apartment blocks.

This

view seems to sum up the state of play in Kyrgyzstan and also

in large parts of central Asia in general. The situation is

not completely hopeless but a great deal of investment will be

needed if the region is to fulfil its potential.

|